Helicobacter pylori is a gram-negative bacterium that colonizes the gastric mucosa of roughly half of the world’s inhabitants.1 The vast majority (80-85%) of H. pylori carriers never experience symptoms or complications; yet colonization can result in chronic gastritis or inflammation of the stomach lining at the site of infection. This inflammation is considered to be a major risk factor in the development of gastric ulcers, duodenal ulcers, mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma, and gastric adenocarcinoma.2 Approximately 10% of those colonized by H. pylori will ultimately develop peptic ulcer disease, and the risk of developing gastric cancer is increased by three to six times with chronic H. pylori infection.3,4

Research has demonstrated that Helicobacter pylori coevolved with humans as a member of the indigenous gastric microbiota.5 In fact, H. pylori once colonized almost every adult human on the planet, and only in the last century have colonization rates been declining.6 This decline is noted particularly in developed countries where H. pylori now infects just 30 to 40 percent of the adult population, compared with a prevalence of 80 to 90 percent in the developing world.4 Historically, colonization during childhood was the norm; today fewer than 10% of U.S. children are colonized by H. pylori. Current rates of colonization reflect both diminishing transmission — due to changes in sanitation and population demographics — and increasing antibiotic usage, both for H. pylori eradication and for unrelated concerns.6

Because H. pylori causes overt gastric disease in only a small subset of human carriers, researchers have begun to consider a potential mutualistic or protective role that H. pylori may play in the natural stomach ecology. Preliminary evidence suggests that H. pylori may play an important role in protecting from some diseases. Animal studies suggest that H. pylori has evolved to skew the adaptive immune response toward immune tolerance, which tends to promote persistent infection and to inhibit autoinflammatory and allergic T-cell responses.7 Human epidemiological studies show that H. pylori colonization is associated with lower incidences of childhood asthma,8 allergic rhinitis,9 and atopic dermatitis.10 In addition, inverse relationships between H. pylori status and risk of developing inflammatory bowel disease and celiac disease have been documented.11,12 The prevalence of H. pylori in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is also lower than in those without reflux disease.13 It has been postulated that H. pylori protects against GERD and its consequences, including esophageal adenocarcinoma, via its regulatory effects on gastric hormone secretion and gastric pH.14 Natural colonization with H. pylori is even hypothesized to play a role in preventing the development of early-life obesity via its regulatory effect on energy homeostasis mediated by gastric hormones such as leptin and ghrelin.15

When to Test

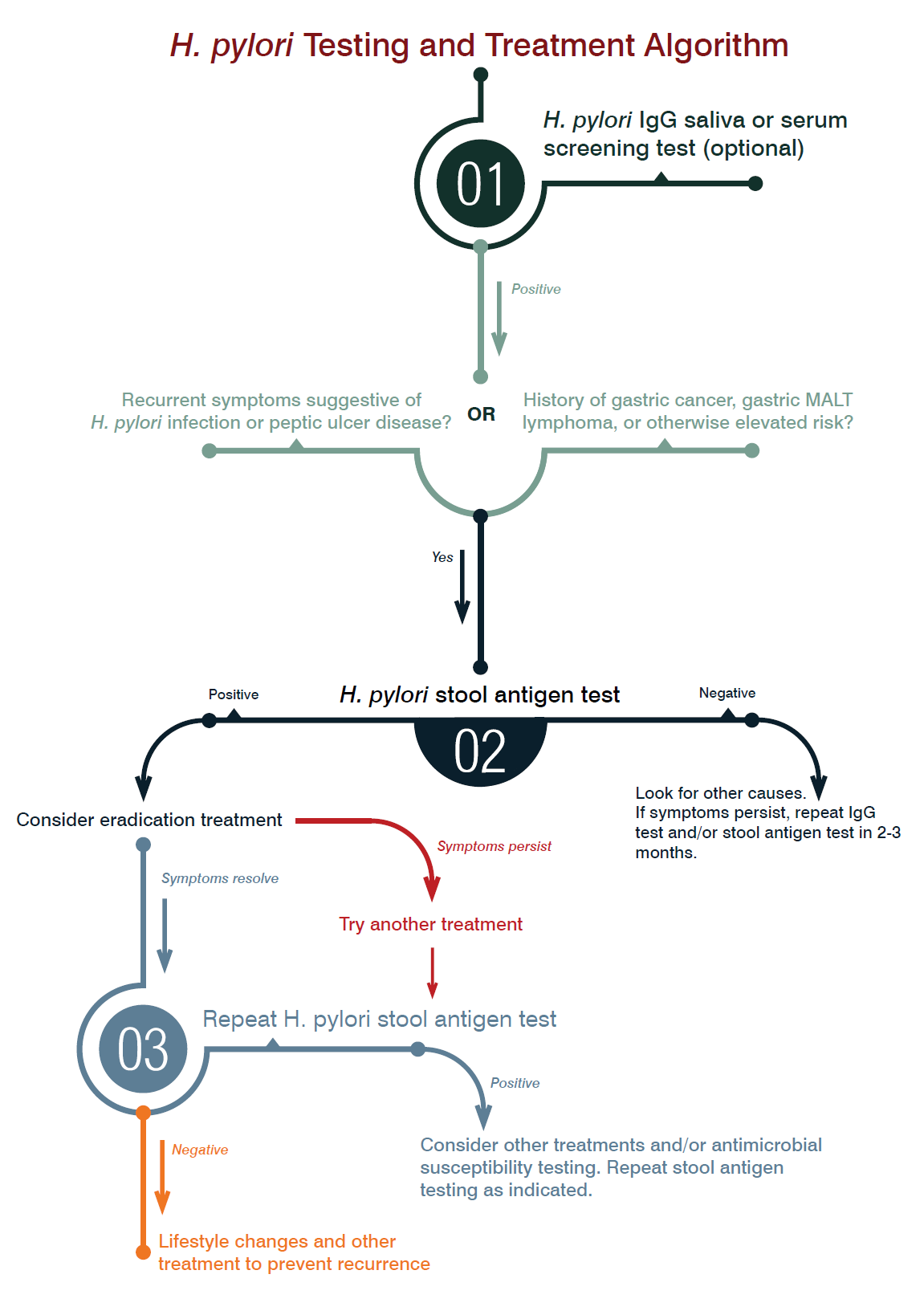

According to consensus guidelines from the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG), laboratory testing for diagnosis of H. pylori infection should always precede eradication treatment and should only be performed if the clinician plans to offer treatment for positive results. Specifically, H. pylori diagnostic testing is most indicated for patients with active peptic ulcer disease, a past history of peptic ulcer disease, lowgrade gastric MALT lymphoma, or after resection of early gastric cancer. The ACG also recommends diagnostic testing for patients with uninvestigated dyspepsia.16 Testing guidelines for patients with non-ulcer dyspepsia, GERD, and unexplained iron deficiency anemia remain controversial, as do those for patients using NSAIDs, and for populations at higher risk for gastric cancer.16

Which Test to Choose

There is no single laboratory test that is considered the gold standard for diagnosis of H. pylori infection. Choice of test should be influenced by clinical presentation and associated risks. Invasive testing methods (i.e., histology, rapid urease testing, and culture) are conducted after endoscopy using biopsy specimens and are reserved for patients with suspected gastric malignancy or evidence of upper GI bleeding.16 Short of endoscopy, several less invasive laboratory tests are available to aid in diagnosis. These include serum and salivary antibody tests, urea breath tests, and the H. pylori stool antigen test.

Antibody tests rely upon the detection of IgG antibodies to H. pylori in serum or saliva. IgG antibodies typically become present approximately 21 days after infection and can remain present long after eradication, limiting their utility in documenting successful treatment. Advantages of H. pylori IgG antibody tests include their low cost, widespread availability, and rapid results. Yet, due to the frequency of false positives, these tests cannot be relied upon for accurate diagnosis. Even so, they are useful for screening since their negative predictive value is very high.16

DiagnosTechs currently offers salivary H. pylori IgG as a screening test. Because IgG antibody tests do not distinguish between active infection and past exposure, we do not recommend that the saliva H. pylori IgG test be used as an independent measure to guide treatment. While IgG antibody testing is no longer recommended for primary diagnosis or for treatment follow-up, our salivary H. pylori IgG test remains useful for screening purposes due to its simplicity and cost-effectiveness. Based on clinical findings, a positive result on the salivary H. pylori IgG test may be followed up with a more definitive test to confirm active infection. Tests for active infection include the urea breath tests and the H. pylori stool antigen test. Urea breath tests detect the highly active urease activity of H. pylori. Breath tests can be performed using either radioactive (13C) or non-radioactive (14C) isotopes, and they rely on detection of labeled CO2 in the breath after ingestion of carbonlabeled urea. Although urea breath testing is highly sensitive and specific, it has a number of significant drawbacks: it is time-consuming, expensive, requires specialized detection equipment, and involves the ingestion of isotopically-labeled urea. Additionally, test sensitivity is decreased by medications that suppress or inhibit H. pylori or decrease urease activity, including bismuth containing compounds, antibiotics, and proton pump inhibitors (PPIs).16

Helicobacter pylori stool antigen testing serves as a more practical alternative to urea breath testing and gives similar high levels of sensitivity and specificity. This test detects H. pylori antigen in stool specimens based on enzyme immunoassay utilizing a monoclonal anti-H. pylori antibody. Stool antigen testing is a noninvasive and convenient method to detect active infection in patients of all ages, and it can be used to confirm diagnosis, for therapeutic monitoring, and for verification of eradication post-treatment. Although stool antigen testing may be effective in confirming eradication as early as 14 days after treatment, current guidelines recommend waiting at least four weeks after treatment is complete before follow-up testing is performed.16

As with urea breath testing, drugs used to treat H. pylori (such as antimicrobials, PPIs, and bismuth preparations) may lead to false negative stool antigen test results due to temporary suppression of infection. The rate of false negatives on stool antigen testing, however, is lower than the rate associated with urea breath testing. In clinical situations where patients are unable or unwilling to stop PPI therapy two weeks prior to stool antigen testing, positive test results can be interpreted as true positives, but negative results may represent false negatives and should be confirmed with repeat testing two weeks after stopping PPI therapy.17

Risks and Benefits of Treatment

A recent research review found significant evidence for clinical benefits with eradication treatment in cases of H. pylori-positive gastric and duodenal ulcers, MALT lymphoma, early gastric cancer, and in those with H. pylori-positive persistent dyspepsia. This same review noted supportive evidence for treatment in cases of atrophic gastritis, long-term NSAID and aspirin use, iron-deficiency anemia, and for cancer prevention in patients with a family history of gastric cancer.18 Treatment of H. pylori infection in cases of non-ulcer dyspepsia and GERD remains controversial. Eradication of H. pylori may be associated with improvement of GERD symptoms in patients with antral-predominant gastritis, but worsening of symptoms in patients with corpus-predominant gastritis.18

Combination antibiotic protocols to eradicate H. pylori are the standard of care in patients who are shown to be infected and who have known H. pylori-related disease. In a meta-analysis of comparative trials, however, antibiotic eradication was not more effective than anti-acid drugs given alone at healing gastric ulcers, and was only slightly superior to anti-acid drugs alone for healing duodenal ulcers. Ongoing anti-acid drug therapy was also found to be just as effective as H. pylori eradication at 6-24 months follow-up for maintaining remission.19

Ultimately, a healthy gastric mucous layer is critical for protecting against gastritis and ulceration. Enzymes produced by H. pylori are known to damage normal gastric mucus, yet many factors besides H. pylori may also damage this protective mucus layer, including NSAIDS, corticosteroids, stress, smoking, and low intake of dietary fiber.20 Although chronic inhibition of stomach acid secretion may lead to symptom resolution and disease remission, restoring the protective function of the mucus layer is critical to healing and long-term relapse prevention. Given that symptomatic improvement and ulcer healing may be influenced by factors other than H. pylori eradication, some researchers argue that antibiotic protocols for eradication of H. pylori in peptic ulcer patients — and patients with symptoms of dyspepsia generally — are not necessarily warranted and may even be detrimental, especially given the negative outcomes that H. pylori eradication may engender. In this more cautionary view, treatment to eradicate H. pylori should be reserved for patients with recurrent H. pylori-related symptoms or complicated disease.21

Widespread antibiotic resistance in H. pylori infection is also a growing concern. Attempts at eradication that fail often elicit secondary antibiotic resistance. Increasing rates of antibiotic resistance with the associated potential to develop more pathogenic bacterial strains should further caution against overtreatment with conventional antibiotics.22

How to Treat

Although comprehensive natural treatment protocols have not yet been studied in comparison to conventional antibiotic protocols, many individual natural treatments do show promise for inhibition and/or eradication of H. pylori. An overview of both conventional protocols and natural treatment options may be found in our ChronoBiology #12 (Summer 2012) newsletter article ‘Therapy Corner: Helicobacter pylori’. To summarize, notable natural treatments include cranberry juice, garlic, berberinecontaining herbs such as Hydrastis canadensis, vitamin C, and various probiotic strains; and preventive dietary interventions include broccoli sprouts, green tea, and live fermented foods.23

Additional treatments include the Chinese herbal formula ‘He wei tang’ (Decoction for Regulating the Stomach). An open label clinical trial of this formula given by itself for 4-6 weeks in patients with chronic atrophic gastritis demonstrated an impressive 68% eradication rate among patients who were H. pylori positive at baseline.24

Other botanical medicines showing promise in human clinical studies include Nigella sativa (also known as blackseed, black cumin, or black caraway) which eradicated H. pylori in 67% of patients when given concurrent with a PPI (comparable to standard triple therapy in this study)25; Pistacia lentiscus var. chia (mastic gum), which eradicated H. pylori in approximately 35% of patients when given independently (but not when given with PPI therapy)26; and Glycyrrhiza glabra (deglycyrrhizinated licorice root extract) which eradicated H. pylori in approximately 50% of patients when given independently.27 It is notable that both mastic gum and deglycyrrhizinated licorice root have also been shown to relieve symptoms of dyspepsia28, 29 and to promote ulcer healing.30, 31, 32

Other natural agents to consider include N-acetyl cysteine (a mucolytic agent that decreases mucus viscosity to facilitate greater contact between antimicrobial agents and H. pylori),33 zinc carnosine (a mucosal protective agent),34 and lactoferrin (a natural antimicrobial).35 All of these have demonstrated improved eradication rates when given alongside conventional treatment protocols. It is notable that zinc carnosine may also promote ulcer healing.36 Additional therapies for consideration include melatonin,37 L-tryptophan,37 and fresh green cabbage juice,38 all of which have been found to effectively speed ulcer healing in clinical studies.

In Conclusion

The debate over appropriate testing and treatment guidelines for H. pylori-related conditions will move forward only with a clearer understanding of the unique role that H. pylori plays in the human gastric microbiota. Concerns regarding potential negative health consequences that may ensue subsequent to aggressive H. pylori eradication should caution against overtreatment of infection. Even so, appropriate diagnostic testing and treatment for those suffering from recurrent H. pylori-related symptoms or chronic disease will remain an essential recommendation.

In patients for whom testing is indicated clinically or due to a positive IgG screening test, the H. pylori stool antigen test is a convenient, noninvasive means for diagnosing active infection and monitoring treatment outcome. The H. pylori stool antigen test gives fewer false positives when compared with screening IgG antibody tests and is comparable to the urea breath test in terms of overall diagnostic accuracy. Stool antigen testing is also the most cost-effective strategy for confirming H. pylori eradication post-treatment.

References

- Crowe SE. Bacteriology and epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection. UpToDate Web site. www.uptodate.com/contents/bacteriology-and-epidemiology-of-helicobacter-pylori-infection. Published November 22, 2013. Accessed August 20, 2014.

- Crowe SE. Pathophysiology of and immune response to Helicobacter pylori infection. UpToDate Web site. www.uptodate.com/contents/pathophysiology-of-and-immune-response-to-helicobacter-pylori-infection. Published October 10, 2013. Accessed August 20, 2014.

- Crowe SE. Association between Helicobacter pylori infection and gastrointestinal malignancy. UpToDate Web site. www.uptodate.com/contents/association-between-helicobacter-pylori-infection-and-gastrointestinal-malignancy. Published July 14, 2014. Accessed August 20, 2014.

- Ables AZ, Simon I, Melton ER. Update on Helicobacter pylori treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2007;75(3):351-8.

- Linz B, Balloux F, Moodley Y, et al. An African origin for the intimate association between humans and Helicobacter pylori. Nature. 2007;445(7130):915-8.

- Blaser MJ. Who are we? Indigenous microbes and the ecology of human diseases. EMBO Rep. 2006;7(10):956-60.

- Arnold IC, Hitzler I, Müller A. The immunomodulatory properties of Helicobacter pylori confer protection against allergic and chronic inflammatory disorders. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2012;2:10. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2012.00010.

- Chen Y, Blaser MJ. Helicobacter pylori colonization is inversely associated with childhood asthma. J Infect Dis. 2008;198(4):553-60. doi: 10.1086/590158.

- Blaser MJ, Chen Y, Reibman J. Does Helicobacter pylori protect against asthma and allergy? Gut. 2008;57(5):561-7. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.133462.

- Herbarth O, Bauer M, Fritz GJ, et al. Helicobacter pylori colonisation and eczema. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2007;61(7):638-40.

- Luther J, Dave M, Higgins PD, Kao JY. Association between Helicobacter pylori infection and inflammatory bowel disease: a meta-analysis and systematic review of the literature. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16(6):1077-84. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21116.

- Lebwohl B, Blaser MJ, Ludvigsson JF, et al. Decreased risk of celiac disease in patients with Helicobacter pylori colonization. Am J Epidemiol. 2013 Dec 15;178(12):1721-30. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwt234.

- Cremonini F, Di Caro S, Delgado-Aros S, et al. Meta-analysis: the relationship between Helicobacter pylori infection and gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18(3):279-89.

- Blaser MJ. Who are we? Indigenous microbes and the ecology of human diseases. EMBO Rep. 2006;7(10):956-60.

- Blaser MJ, Falkow S. What are the consequences of the disappearing human microbiota? Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7(12):887-94. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2245.

- Chey WD, Wong BC; Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. American College of Gastroenterology guideline on the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(8):1808-25.

- Crowe SE. Indications and diagnostic tests for Helicobacter pylori infection. UpToDate Web site. www.uptodate.com/contents/indications-and-diagnostic-tests-for-helicobacter-pylori-infection. Published April 25, 2014. Accessed August 20, 2014.

- Hung IF, Wong BC. Assessing the risks and benefits of treating Helicobacter pylori infection. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2009;2(3):141-7. doi: 10.1177/1756283X08100279.

- Ford AC, Delaney BC, Forman D, Moayyedi P. Eradication therapy for peptic ulcer disease in Helicobacter pylori positive patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(2):CD003840.

- Yarnell E. Peptic ulcer disease. In: Yarnell E. Natural Approach to Gastroenterology. 2nd ed. Seattle, WA: Healing Mountain Publishing; 2011:1133-1171.

- Yarnell E. Helicobacter pylori. In: Yarnell E. Natural Approach to Gastroenterology. 2nd ed. Seattle, WA: Healing Mountain Publishing; 2011:1173-1210.

- Graham DY, Fischbach L. Helicobacter pylori treatment in the era of increasing antibiotic resistance. Gut. 2010;59(8):1143-53. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.192757.

- Webb B. The Therapy Corner: Helicobacter pylori. ChronoBiology Letter. 2012;(12):4-6. www.diagnostechs.com/Literature/ChronoBiology/Chrono_12.pdf

- Ji WS, Gao ZX, Wu KC, Qiu JW, Shi BL, Fan DM. Effect of Hewei-decoction on chronic atrophic gastritis and eradication of Helicobacter pylori. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11(7):986-9.

- Salem EM, Yar T, Bamosa AO, et al. Comparative study of Nigella sativa and triple therapy in eradication of Helicobacter pylori in patients with non-ulcer dyspepsia. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2010;16(3):207-14. doi: 10.4103/1319-3767.65201.

- Dabos KJ, Sfika E, Vlatta LJ, Giannikopoulos G. The effect of mastic gum on Helicobacter pylori: a randomized pilot study. Phytomedicine. 2010;17(3-4):296-9. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2009.09.010.

- Puram S, Suh HC, Kim SU, et al. Effect of GutGard in the management of Helicobacter pylori: a randomized double blind placebo controlled study. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:263805. doi: 10.1155/2013/263805.

- Dabos KJ, Sfika E, Vlatta LJ, Frantzi D, Amygdalos GI, Giannikopoulos G. Is Chios mastic gum effective in the treatment of functional dyspepsia: a prospective randomised double-blind placebo controlled trial. J Ethnopharmacol. 2010;127(2):205-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.11.021.

- Raveendra KR, Jayachandra, Srinivasa V, et al. An extract of Glycyrrhiza glabra (GutGard) alleviates symptoms of functional dyspepsia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012:216970. doi: 10.1155/2012/216970.

- Al-Habbal MJ, Al-Habbal Z, Huwez FU. A double-blind controlled clinical trial of mastic and placebo in the treatment of duodenal ulcer. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1984;11(5):541-4.

- Turpie AG, Runcie J, Thomson TJ. Clinical trial of deglycyrrhizinized liquorice in gastric ulcer. Gut. 1969;10(4):299-302.

- Larkworthy W, Holgate PF. Deglycyrrhizinized liquorice in the treatment of chronic duodenal ulcer: a retrospective endoscopic survey of 32 patients. Practitioner. 1975;215(1290):787-92.

- Karbasi A, Hossein Hosseini S, Shohrati M, Amini M, Najafian B. Effect of oral N-acetyl cysteine on eradication of Helicobacter pylori in patients with dyspepsia. Minerva Gastroenterol Dietol. 2013;59(1):107-12.

- Kashimura H, Suzuki K, Hassan M, et al. Polaprezinc, a mucosal protective agent, in combination with lansoprazole, amoxycillin and clarithromycin increases the cure rate of Helicobacter pylori infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999;13(4):483-7.

- Zou J, Dong J, Yu XF. Meta-analysis: the effect of supplementation with lactoferrin on eradication rates and adverse events during Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy. Helicobacter. 2009;14(2):119-27. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2009.00666.x.

- Kato S, Tanaka A, Ogawa Y, et al. Effect of polaprezinc on impaired healing of chronic gastric ulcers in adjuvant-induced arthritic rats–role of insulin-like growth factors (IGF)-1. Med Sci Monit. 2001;7(1):20-5.

- Celinski K, Konturek PC, Konturek SJ, et al. Effects of melatonin and tryptophan on healing of gastric and duodenal ulcers with Helicobacter pylori infection in humans. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2011;62(5):521-6.

- Cheney G. Rapid healing of peptic ulcers in patients receiving fresh cabbage juice. Calif Med. 1949;70(1):10-5.